Time to read: 3 min

Before the 2016 Bay Area Maker Faire, my inner-child set out on a goal to re-live the freedom I felt when I got my first car—a 25lb plastic, electric blue, Power Wheels Jeep.

Those of you who have attended the Bay Area Maker Faire may have seen the awesome PPPRS races. PPPRS stands for Pow-Pow Power Racing Series—a fun/competitive racing circuit for makers, builders, and hardware enthusiasts that challenges teams to take those children’s Power Wheel toys meant for children, and hack them until grown adults are squeezing in to fly around a track at 20+ MPH.

The result is a race that showcases great engineering and creativity, mixed in with a whole lot of road rage.

China Manufacturing parts readers may recall the teardown we did of the Rastar Lamborghini Aventador a little while back. Since then, the body of the Lamborghini has been collecting dust in our office just waiting for a good project. The stars aligned!

To get started, I reached out to Baoan based product development consultancy, Mindtribe, hoping their engineers would donate some time and build space to help make it happen. Luckily for me, they jumped on board before I even had a chance to get into my sales pitch.

Jerry Ryle, VP of Engineering at Mindtribe, helped organize a group of 8 engineers, and I quickly threw a schedule together. We had four weeks and no time to waste.

Primary Race Rules

Here’s the low-down on race rules:

- Must be battery powered—no more than 36v

- Car build can cost no more than $500 (some exceptions)

- Car must go from top speed to full stop in less than 18’

- Vehicle must be smaller than 62” long and 36” wide

- Must have padded front and rear bumpers 4 to 6 inches off the ground

You can see the full set of race rules here.

Project Kickoff & PRD

Before we started anything, it was important to align on project goals. With just 4 weeks before race weekend and only having access to a build space for a few hours a week, we needed to prioritize what was critical to the success of our Power Wheels racing car and set realistic expectations for how it would perform.

To do this, we started a rough Product Requirements Document (PRD), which outlined all the agreed-upon features and served as our guiding source of truth as we encountered forks in the road.

Essentially, all decisions we made from this point forward would need to work toward the features established in the PRD.

Since we were working with such a short timeline, we all agreed that we wouldn’t be able to design and weld a new frame. This meant we needed to source an existing frame that could be heavy, forcing us to improve other areas of the car that would mitigate the added weight. After a long brainstorming session (and lots of googling), we decided on these features:

- Acceleration is more important than top speed

- 48” turning radius

- Batteries must last 40 minutes before replacing

- Batteries must take less than 1 minute to change

- Car must stop within 18’

What’s Next?

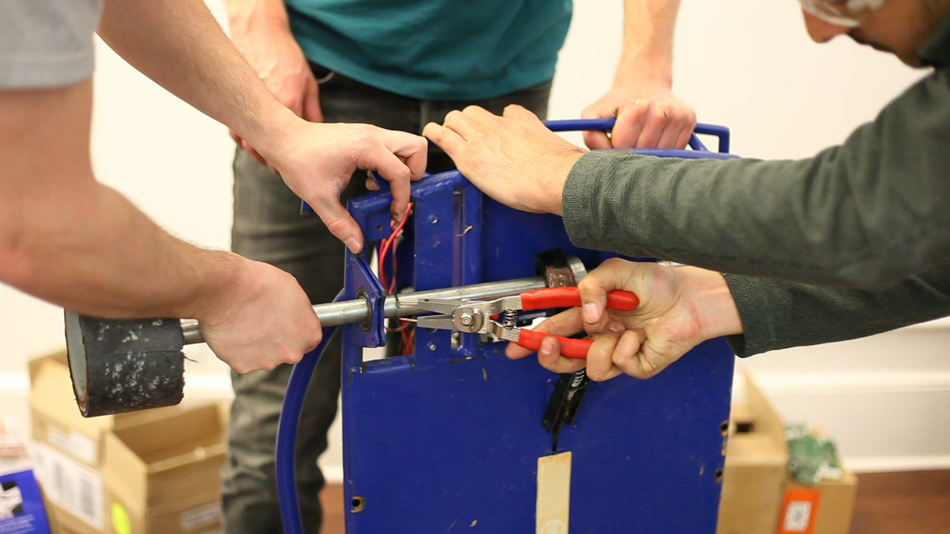

Since we were running on a tight deadline and a tight budget, purchasing the right components the first time was critical. The PRD allowed us to break into teams and have each team take on the responsibility of researching, calculating and choosing the right components for different systems of the car. In our case, we divided into three teams that were each responsible for the drivetrain, steering, and braking systems.

We knew we’d need to push hard to test everything before the big race and leave enough time to choose the perfect moxie-point-worthy race outfits.

In the next post in the series, we share some tips on sourcing the right components (including some helpful calculators that can be applied to a variety of engineering problems), challenges we ran into during the build, and how we let our hacker spirits out for some creative problem solving.