Time to read: 6 min

In an engineering utopia, every project would come in on time and under budget—and, of course, be delivered by a unicorn. Two of these are possible, despite all three being rare. But few projects are planned well, so we end up with unrealistic expectations and often don’t figure that out until the project is 80% through the original timeline and nowhere near 80% complete. How can you solve this perennial dilemma and introduce more predictability into your design process?

The solution is a phased program plan. Surprisingly, even though every product is unique, the process for developing an idea into a market-ready product always follows a similar pattern, and following a standard project plan increases predictability in product development. Breaking down complex projects into smaller phases, like breaking down a cross-country road trip into shorter legs, you can more easily predict the time and cost for your projects, arriving at your destination—project launch—with a smile.

Phased Project Plan Overview

Two of the biggest reasons projects break budgets are: a) Estimating time and cost for a large project is too complex to handle as a single piece; and b) it’s tempting to jump around, completing parts of the detailed design before a spec is complete, or adding features after the product is already mostly complete. A phased program plan solves both of these problems.

First, by following along the same steps for every development project—and tracking the time required for each phase—the task of estimating budget for these small phases becomes much simpler (though, sadly, never simple). Second, once each phase is completed, that part of the project is done; if you do decide to revisit past project phases, both you and your managers know you’ll need to adjust the budget and timeline to accommodate the addition.

With all this magic, how do you implement a phased product plan for your product? The beginning is very simple: Start with a product manifesto.

Problem Definition or Product Manifesto

Before you can start planning your project—before you even commit to a project, and certainly before you can begin developing it—you need to take the time to answer one question: What is its purpose?

For simple products, this can be a really simple answer. If you’re designing airplanes, this answer will be more multi-faceted. For any product, this is the starting point. You’ll get into highly technical specifications at the beginning of the actual development work, but for now you need to develop a high-level overview of what problem the product is going to solve and how it’s different than the competition. Make this as clear and concise as possible—you want this to be your guiding light for both planning the project and developing the product.

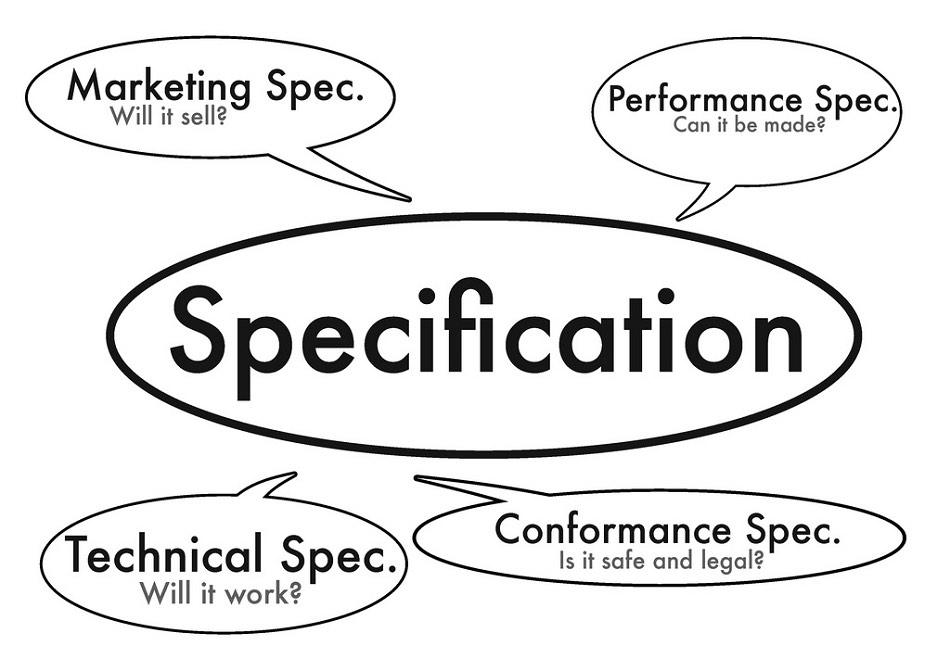

Specification Development

Now that you know where your project is going, you can begin the planning in earnest, and the first phase to plan is the specification development. This is often a phase where it’s easy to skimp, but investing the time up front to create a really good specification document will make every phases afterward smoother, so it’s well worth budgeting enough time to create a really good document with all the necessary research.

What makes a good specification? Pass-fail requirements. Writing a specification is largely a matter of taking soft, fuzzy desired features and translating those into hardline technical requirements. “Lightweight” is a useless requirement; “under three pounds” is a requirement to which you can design.

How long will you need to plan on this phase taking? That depends on the product, but for complex products, this phase can take hundreds of man hours. Plan to research standards for different requirements and possibly to do testing or in-depth research as part of the specification development. These requirements will become your testing standard in later phases, so budget enough time to get this phase right.

Concept Development

Concept development is the fun phase; it’s what many of us had in mind when we became engineers, and it’s the part Hollywood shows as a quick-moving montage of whiteboard sketches and high fives. For each concept area, plan to follow the same basic steps of brainstorming designs and comparing the designs to your specification for selection, but keep in mind that this phase can also have miniature development cycles entirely encompassed in the design, so you may also be creating mockups of different concepts to test out key features.

Detailed Design

Detailed design takes the concept (or concepts) you’ve developed and creates designs ready for prototyping and testing. The bulk of the development time will be spent in this phase, and as the detailed design is being developed, you may also be doing some small tests to validate parts of the design.

This is also the part of development where you’ll be handling fine-grain refinement, selection of off the shelf parts, and making your design easy to manufacture—everything to have the concepts ready for production. With such a massive scope, this is the part of the project that typically gets underestimated, so be sure to have some in-depth conversations with experienced members of your team when planning time and budget for this phase.

Iterative Refinement

Great designs require multiple rounds of testing and refinement, and you’ll need to build that time into your plan from the start. With more details in our article on testing, keep in mind that even for simple products you should plan on three to four iterations of “prototype-test-refine” for the complete design, before everything feels right and functions well.

Preparing the Product for Manufacture

And once your product is functioning well, it’s worth reviewing the design again to ensure that it will transition to mass production easily. Just keep in mind that even though you’ll need to do this final review of the design before moving forward to production, design for manufacture (DFM) and design for assembly (DFA) should be elements of the design, even from the concept development stage. If you have a good team of experienced designers and engineers and kept this as a polestar during the entire design phase, then you won’t need to plan too much time for this part of development, but if your team is less experienced, be sure to budget in enough time for further changes at this stage.

Getting Manufacturing Quotes

Putting together a request for quote (RFQ) feels wonderfully final the first time you do it, and nearly insignificant every time afterward. The manufacturing team receiving your RFQ will almost certainly have more experience in their field than your team, so be sure to allow time for feedback on the manufacturability, and plan on making some changes before the design is completely final.

Transitioning to Production

Once your product is at the manufacturer, it’s going to be time for some celebration. Budget time for your team to take the vacations they’ve been putting on hold, to catch up on sleep, to relax a little—and then plan on getting the team back to work. Managing a product during its production phase has an entirely different set of challenges, and you can look forward to an upcoming article for more information on that (sign up here to get the update as soon as it comes out).

Estimating Time and Resources

Now that we’ve mentally traveled through the whole development process, it’s time to return to the beginning: the project plan. How do you know how much time and money to allocate to each phase?

Unfortunately, there is no easy answer, and the best solution is to rely on the experience of your team. Break down the process in your project plan in as much detail as you can, and then speak with each team member to get estimates for each tiny chunk of work.

However, don’t take their estimates at face value when you’re adding up hours required for the project; it helps to compare their past predictions to actual work time to see how you’ll need to adjust their estimates. Does Tom always promise things in two days but give them to you in three? Plan on 50% extra time added on his estimates. Does Susan always deliver a couple days ahead of schedule? Adjust accordingly.

Finally, give yourself a small amount of margin in each phase, just in case you get a little behind. If you don’t need it in that phase, great! You have it for a future phase, and your clients are thrilled. How much should you allow? Again, that’s going to be based on experience with your team, but I usually add in about 15-20% when I’m working alone, and I’ve yet to receive complaints that I’m too early.

Planning Your Project

Maybe we can’t have unicorn delivery, but by planning your project to closely follow the steps above, you can achieve that mystical on-time, under-budget project. Are you just beginning your product development journey? Sign up here to have great design tips and technical articles delivered right to your inbox. Or are you scrambling to finish out a project that’s short on time? Check out our next-day prototyping services to help you get back on track!