Time to read: 6 min

Here in the Bay Area we probably have the greatest concentration of electronic gadgets, and the people who make them, this side of the planet. That can be a problem when it comes to parenting—even if you hide all your devices under your sofa, your kids will still come home raving about their best friend’s latest coolest thing.

Enter Jabber, the modern non-connected, interactive toy that gets your kids to come outside and play.

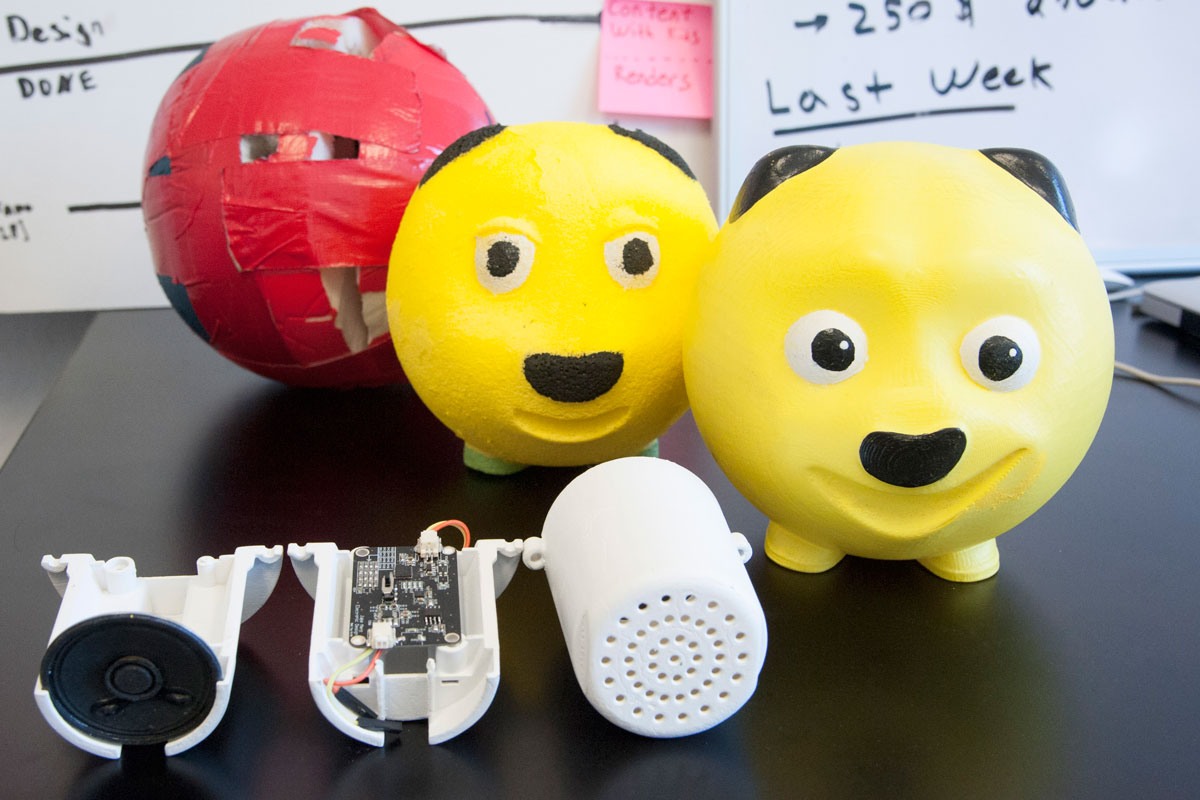

From a kid’s standpoint, Jabber is a talking ball-shaped panda. Or a panda-shaped ball.

From a mechanical engineering standpoint, it’s a wonderfully simple and playfully designed device that can sense what’s going on with it, determine how to respond, and on top of that take some serious punishment (stomping, throwing, kicking).

We sat down with the guys who literally rolled with the punches and came out with a pretty cool toy.

An Idea Sparks

Both founders had what anyone would consider good, stable jobs. Brenden was working in product design in Palo Alto and Jack was in green tech. But as tends to happen with entrepreneurs, it just wasn’t quite enough.

“We’re both really interested in creating something that takes an idea to life,” says Brenden. “So we started talking last winter about what we could do and how to do it on our own. We’d meet once a week, brainstorming ideas: what kind of product, what kind of company we wanted to create. It came down to kids’ toys.”

Jack chimes in with the why: “We’re two big kids at heart. We like to build products that are fun to use. So we wanted to build something for kids andparents.”

The pair also wanted to get kids outside to play, away from all those electronic screens. They still wanted to produce a modern toy, but not one connected to wi-fi. Testing a variety of games, Brenden and Jack discovered that the types of games that do well with children are “more chaotic, as in less structured, and get everyone involved,” as Jack describes it.

We had pages and pages of names, and we tested new ones with the kids every other week

“Some of our favorite toys growing up were Bop-it and Furby,” laughs Brenden. When we ask what was it about these toys that made them faves for the founders, Brenden points out the two elements that now define Jabber. “Bop-it is a competitive toy—you can compete with others or yourself, and Jack and I are both competitive people. And Furby is an interactive toy that reacts to you with different movements and speaker output.”

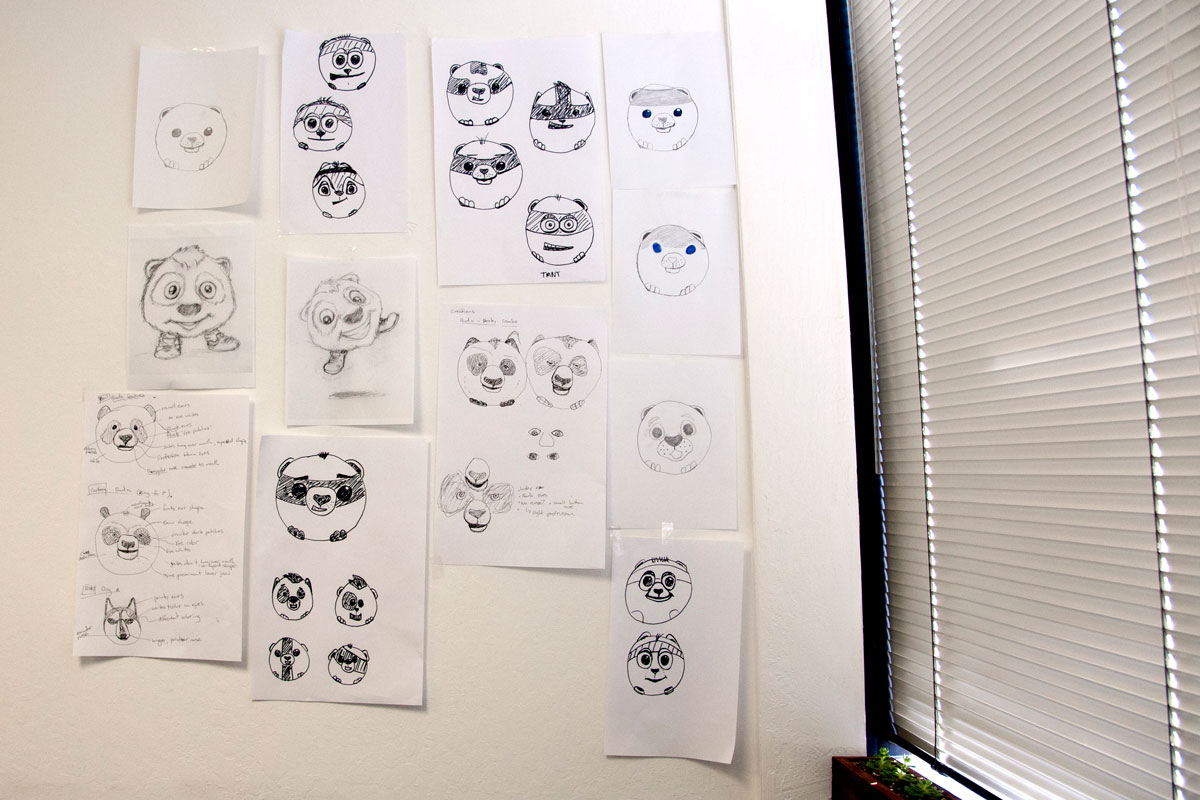

Designing for Kids

The fun factor is a top consideration when you’re designing a toy for kids. No less critical are safety and durability.

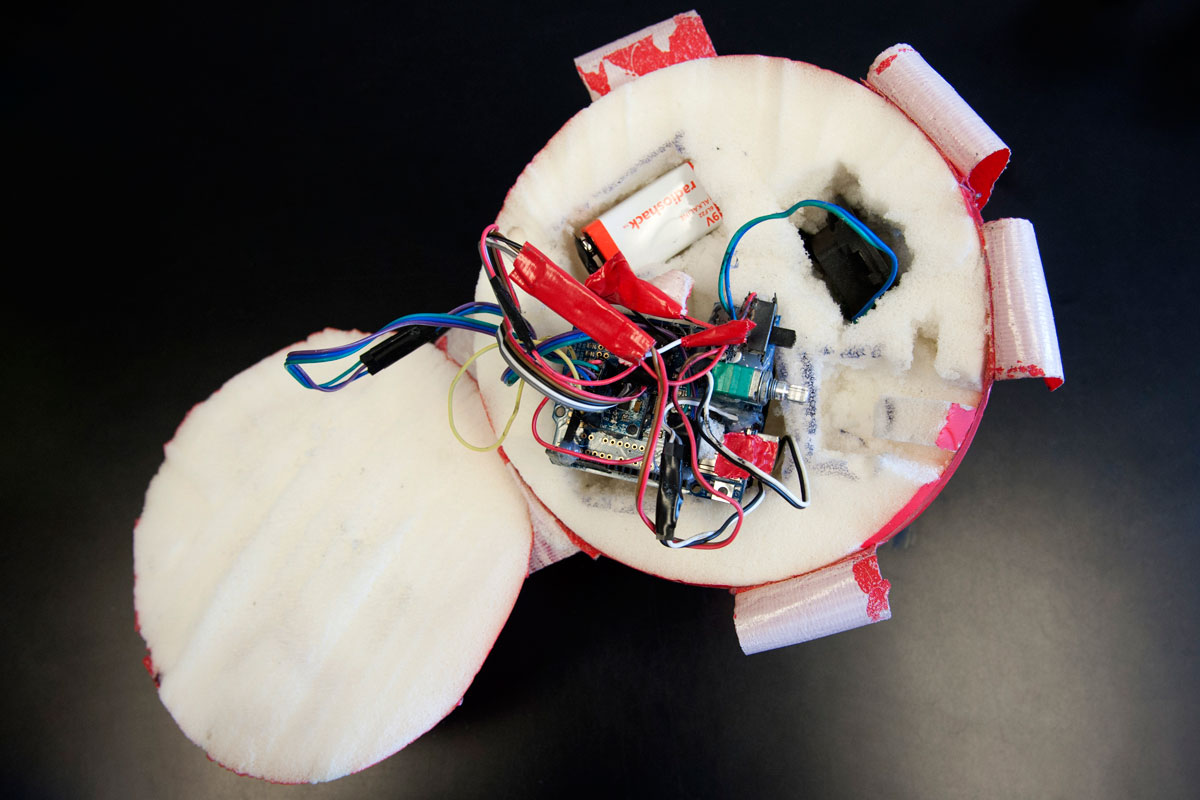

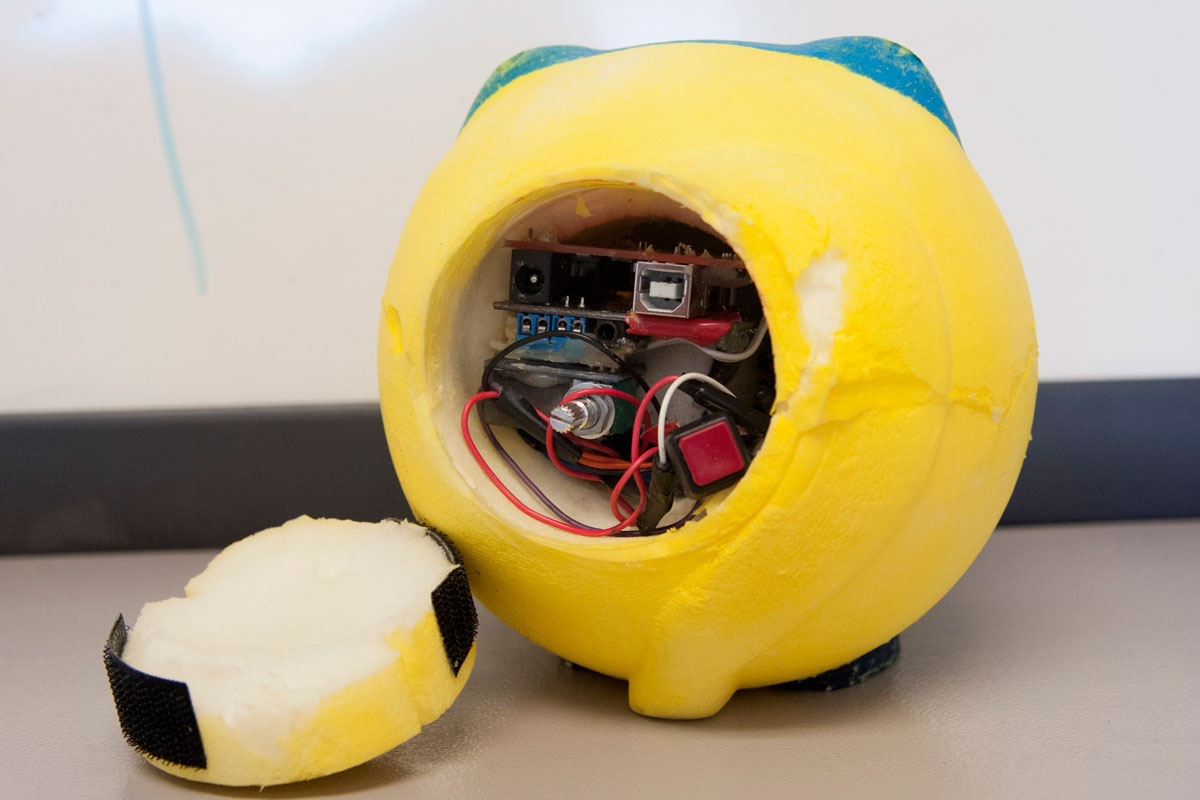

‘We wanted Jabber to be safe first and foremost,” says Jack. “We went with a foam exterior, like a Nerf ball, so it wouldn’t hurt to kick or have it thrown at you, but it would still be durable. And when you play with it, you shouldn’t be able to feel the inside.”

Check, check, and check. Now onto prototyping, in true startup fashion: Brenden’s parents’ garage.

“The prototyping process took us a pretty long time to figure out,” Jack says. “We started by hollowing out Nerf balls and putting in the electronics. Then we needed to find a way to shape the face on the ball. We talked to some local model making shops—one option was to model the face in acrylic and inject the foam into the acrylic block, but that would have cost $6,000, and we didn’t have the budget for that.”

Brenden completes Jack’s thought: “So we talked to Fictiv and they told us we could do the mold with 3D-printed parts. The face would be modeled in a quarter-inch-thick shell, and we’d inject the foam into that. Best part, it would be only a couple hundred dollars.”

But the first try didn’t work quite the way they expected.

Some of the physical tolerances Jack and Brenden had originally specified during the CAD stage didn’t quite match the real world. Some parts needed to be reprinted larger to fit all the electronics. “When you use CAD,” says Brenden, “you need to account for the wiring, so that’s something you need 3D printing for.”

Kids don’t sugarcoat anything—they tell it to you like it is

Then there was the foam.

“Foam,” explains Jack, “is really sticky and expands into the cracks of a 3D-printed mold. We tried urethane, but that stuck just like the foam. So we looked for materials that are smoother and don’t stick, like silicon. We 3D-printed a plastic replica of the ball, then submerged that model in a bucket of silicon. When it dried, we cut out the plastic model, and now we had a hollow silicon chamber that we could inject the foam into. It took a good few weeks to do all this.”

“And then of course we changed the look of the ball,” laughs Brenden.

The World’s Youngest Beta Testers

So what’s it like to work with little ones as your field testers? Jack elaborates.

“It was our first day testing with the first fully functioning prototype. We were really excited. I was explaining the first game and how it’s going to work. A sentence in, a kid took off with the ball, and all the other kids ran after him. He smashed it, stomped on it, and of course it broke, wires went flying.” Why? Well, “because it only had the board and the batteries, no protective structure. So we made an inner housing for the electronics from polycarbonate plastic that can withstand a lot of impact.”

There was the exterior to test, too. As Brenden tells us, “We had hundreds of color schemes and several different physical looks for the ball. The kids would love one and hate the other. Everyone had a different opinion.”

The team also thought the kids might be helpful with coming up with a name for the toy. And they were. Just a little too helpful.

Don’t spend too much time putting together your first prototype, because it’s likely going to get smashed, stomped, or otherwise destroyed

“That was the hardest part. We went through a lot of names,” Jack and Brenden both laugh. “We had pages and pages of names, and we tested new ones with the kids every other week. One five-year-old girl really liked ‘Piope.’ They all wanted to name it after themselves.”

Perhaps most challenging of all was the game design. As Jack explains, “We created elaborate games but the kids wouldn’t engage, so we had to make simple games.”

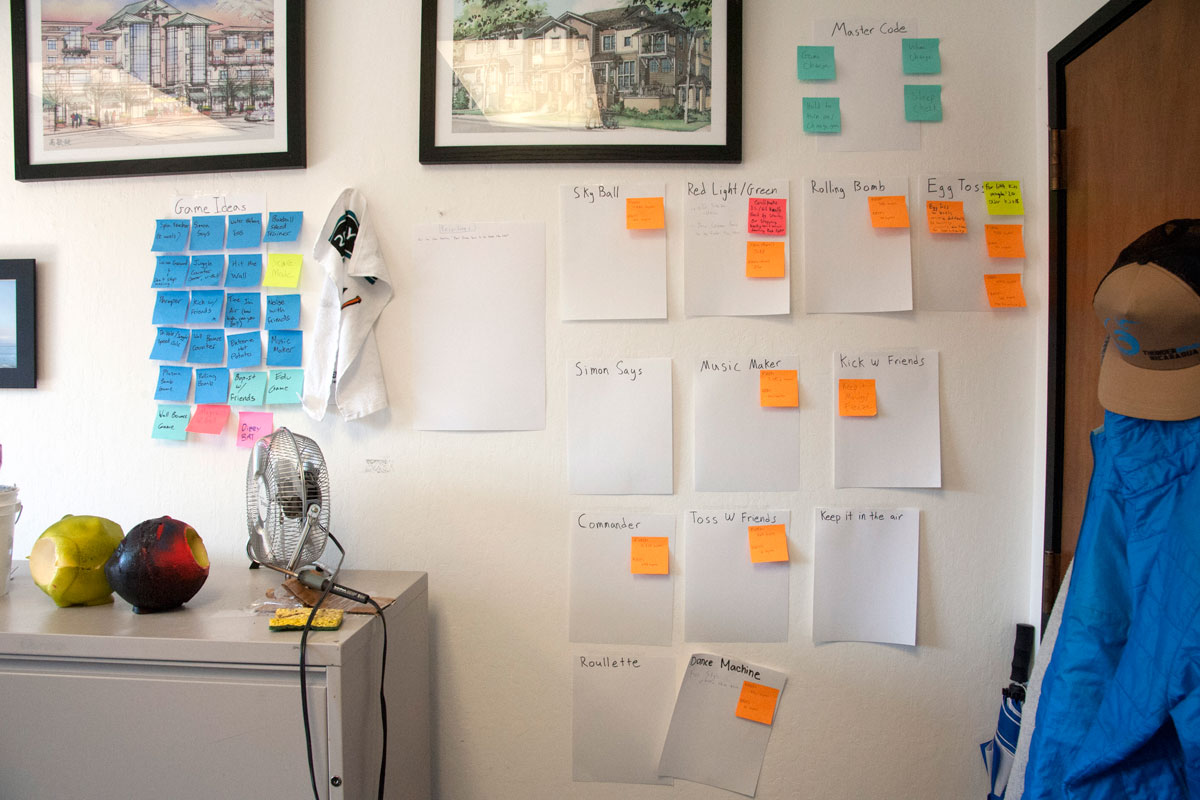

“Yeah, we went through 50 game ideas, and we iterated down,” adds Brenden. “We took a basic game concept like Follow the Leader, we got really excited, and then the kids turned it around to some other game they wanted to play.”

But, even after all that hair-tearing, the team agrees they wouldn’t have it any other way.

“It’s been fun working with kids and doing the testing with them,” says Jack. “You get more genuine feedback. They don’t sugarcoat anything—they tell it to you like it is.”

The Big Takeaway

Unlike products for adults, who (usually) don’t stomp, kick, or throw their electronics around, toys with electronic components need a slightly different approach, and a whole lot of patience. Here are a few words of wisdom from the Jabber creators:

- Make the games simple, relatively unstructured, and multi-player.

- Don’t spend too much time putting together your first prototype, because it’s likely going to get smashed, stomped, or otherwise destroyed.

- Protect the sensitive electronic parts inside the toy, no matter how well you think you’ve designed it.

- Account for all the wiring and assembly constraints when you produce your 3D models.

- Take the time to research and source materials that are tough, safe for kids, and work well together.

- Don’t get discouraged if kids turn down all your ideas. Thank them.